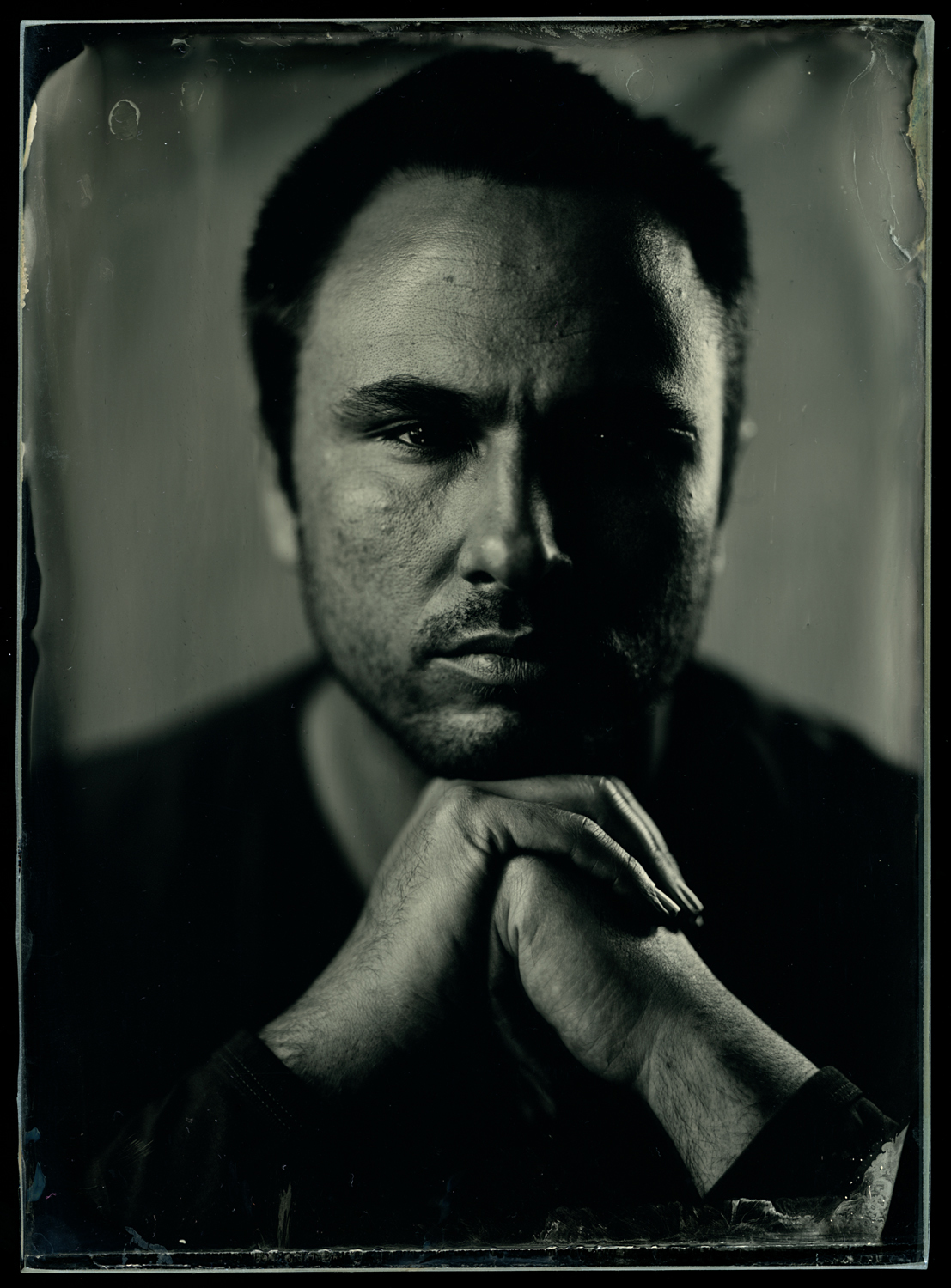

Marko Dejanović

Marko Dejanović was born in Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1982. From 1992 to 1998 he lived as a refugee in Frankfurt, Germany. He studied journalism at the University of Zagreb and has worked for ten years for RTL Televizija as well as for news, commentary and satire portals. Currently he is head of agency at the Newsroom information service. Since late 2014 he has been performing as a stand-up comedian. He is an alumnus of the Academy for Political Development, generation of 2015. In the same year, his novel 'Tickets, Please!' won the Janko Polić Kamov Award for literary excellence and innovation (the only prize in Croatia open to all genres of writing).

Tickets, Please!, novel, Zagreb, 2015

Beelzebub's Memo Pad, short stories, Čekić, Belgrade, 2011

Praises:

About 'Tickets, Please!'

"Skilfully and unsentimentally, Dejanović brings to life universal emotions such as love, the desire for revenge, and the fear of death, and sets them in today’s Croatian reality without recourse to stereotypes. These are unique and at the same time archetypal stories of postwar tragedy, rooted in wartime events and trailing behind like a vow of vengeance despite the amount of time that has passed since". (Critical Review, 5 Books from Croatia, 2016)

SAMPLE TRANSLATION:

Tickets, Please! (excerpt from a novel)

MATTHEW’S SLAP IN THE FACE

‘I’ve used up a lot of time. Quite enough, I reckon. I didn’t keep any aside, although I’m frugal by nature. Then again, the two of you are right: can a person really save time? Is there any point in trying? I don’t know. I only know we can use it up. And I have used up, you see, twenty years and more. I frittered it away just like that. I spent time seeking revenge. Perhaps I shouldn’t have, perhaps it was time wasted. But I had to use it up like that.

‘I don’t know if it’s the same for you two, but I can’t let things go and just put them behind me. That’s how it is even for small things, let alone something like this... If you humiliate me, I have to get my own back. Every day without revenge is like a new spit or slap in the face. A slap is humiliating: you punch someone who’s your equal, but a slap is to put someone in their place.

‘My twenty years began with a slap. If it had just been the slap, I might have been able to forget. Or maybe not... You know that joke?’

We didn’t know it, or at least I didn’t. And I couldn’t even answer if I knew it or not since he didn’t say which joke he meant.

‘Which one?’ the conductor cut in appropriately.

‘The one about the peasants and the Germans.’

‘Go on,’ the conductor said. I couldn’t remember a single joke about peasants and Germans.

‘The Germans are searching a Bosnian village in World War Two. They drag a peasant, his wife and two daughters out of their house and interrogate them. The peasant is helping the Partisans because he is an honest man, but he refuses to say anything.

‘“Speak! Where are the Partisans?” the head Kraut yells.

‘“I don’t know,” the man says with an air of defiance.

‘“Tell us where the Partisans are, or we’ll kill your wife!”

‘“I don’t know!”

‘And the Kraut pushes his wife to her knees and puts a bullet in her head.

‘“Where are the Partisans?” the head Nazi goes again.

‘“I don’t know,” the peasant continues to lie.

‘“Tell us, or we’ll set fire to your house and property!”

‘“I don’t know!”

‘And they set fire to his house and property. He stands there, his daughters too, watching the house burn. Finally it collapses into a fiery heap and the head Nazi asks again:

‘“Where are the Partisans?”

‘“I don’t know,” the peasant says calmly, as if they haven’t just killed his wife and burned down his house.

‘“Listen, we’ll kill one of your daughters if you don’t tell us.”

‘“I have nothing to say,” he answers, as if not fearing for his daughters.

‘And the Kraut takes one daughter and points his pistol at her head.

‘“Where are the Partisans?”

‘“I don’t know.”

‘The pistol goes off and kills the girl. The peasant stands there motionless with his surviving daughter. As if they haven’t destroyed everything before his eyes.

‘“Where are the Partisans?” The head Kraut is angry by now, but the peasant is not.

‘“I don’t know.”

‘“We’ll kill your other daughter if you don’t tell us. We’ll stamp out your bloodline! Where are the Partisans?”

‘“I don’t know.”

‘And they drag the other daughter up in front of him. They don’t shoot her but beat her to death with their jackboots and rifle butts. The peasant can do nothing but look on. He stands there, and in front of him the head German.

‘“Speak! Where are the Partisans?” screams the Kraut.

‘“I don’t know,” the peasant says calmly, which completely infuriates the Kraut.

‘“Speak!” he shouts and hits the man on the cheek with the flat of his hand. The cheek goes red and the peasant holds his fingers to it; his eyes flash and his voice betrays the desire to sink his teeth into the Kraut’s throat:

‘“Oho, so now we’ve started slapping!”’

The conductor burst out laughing; I merely smiled. The joke left me cold. But I nodded to say I understood, while Matthew, still laughing, asked if we realised the full significance of a slap in these parts.

‘You see, Dejanović,’ the conductor remarked when he managed to subdue his laughter.

‘Good point! This joke explains the whole anti-fascist movement and why it was so successful. It’s all in the punchline. It even explains Tito’s legendary “No” to Stalin.’

‘Quite,’ added Matthew. ‘You can walk all over us, burn our land and kill our families. You can do all sorts of things, but don’t slap us. Don’t you dare... You know, a man once slapped me in the face. He didn’t stop at that, but that’s how it started. And I don’t know if I would have ignored the slap if that was the end of it, although I doubt it. It still hurts me today. It was in ‘91. I was living with my parents in Osijek. Now I’m living in Zagreb. But that’s not important. My father was a retired officer of the Yugoslav People’s Army. My mother had retired too. They, my sister and I all lived in the flat. I was about seventeen. My sister had just come of age.

‘I come from a mixed marriage. My old man was Croatian, my mother Serbian, and both as Yugoslav as could be. I didn’t even know their true nationalities until it all started; then I found out my sister and I were half-breeds. Our father assured us it would all blow over, that people were just a bit “brain-fucked”. He brought that word with him from the village in Bosnia where he was born. When someone is brain-fucked it means they’re upset, but their distress is meaningless and won’t have any real effect. Yeah, our father held that people were a bit brain-fucked. Our mother didn’t say anything. She didn’t state an opinion now, nor was she ever in the habit of speaking her mind because her husband was an officer. It was his right to command.

When things started to seethe and churn and people became brain-fucked, my old man remained calm.

‘“I’m a pensioner,” he joked, and then added seriously that he had no intention of getting mixed up in anything stupid, and that this would all blow over; the army would take up position if needs be and say, “Enough!” when it saw that it really was enough. There were those who asked him why he didn’t join in, but my father answered that he wouldn’t get mixed up in politics, and that, if someone were to attack his Osijek, he’d defend it. Until then, he explained, he would have no truck with anything. “I’m a pensioner,” he concluded, half joking, half serious. Then came ’91 and the break-up of the country; no one asked my old man anything any more, and he no longer said anything. Only at home, to us, he’d sometimes repeat that people were brain-fucked, but now even he wasn‘t sure any more. That’s probably why he was mostly silent. He didn’t know what to say, or what to command. Neighbours who we used to be on friendly terms with now avoided us. A cool exchange of “Hello”, “Hello”, was the most it came to. There was no having coffee together, no one asked my parents over, nor did my parents ask anyone to visit. Sometimes the phone would ring. My old man always insisted on answering it himself. He didn’t tell us who called or what they wanted, but we knew they were calling to insult him. Once my sister answered it when he was out. A man asked for dad, and when she said he wasn’t home the man told her to give him a message: that he’d cut his throat and those of his “Chetnik bastards”. We told our father, and he said he’d arranged with a friend from Zagreb to rent his flat. The friend travelled abroad and left the flat empty. My sister was due to start university anyway.

‘“He’ll be vacating the flat some time before summer. Take your brother with you and stay there until all this calms down a bit. Mum will go with you to help you settle in. I’ll stay here to look after the flat here,” our old man ordered. But the friend didn’t vacate his flat before summer; there had been complications and now he didn’t need to leave until sometime in August. My sister went to sit the entrance exam, passed it and returned to Osijek to wait for the beginning of the academic year. Having nothing to do, she just met friends and hung out in cafés. The old man’s orders were postponed until August. He wasn’t happy with the situation, but he didn’t seem worried. The only thing he couldn’t hide was his age. All at once he began to look old, and you could see he was a pensioner.

‘It wasn’t long after we celebrated my sister’s acceptance at the Faculty of Agriculture – a little party at home – that I had to endure my slap. It was early in the morning. Only our parents were awake. A group of men came to the door. Five of them. They squeezed in through the hall. None took off their shoes, although that was a custom.

‘The noise woke me up and I went out. My sister stayed in her room, only opening the door to see what the fuss was about, but our father gestured to her to shut it.

‘The five men were standing in the lounge room: they were young, only a few years older than me. My parents stood opposite them.

‘“Guys, I’m Croatian,” I heard my old man say.

‘“You’re a dickhead, not a Croatian,” the shortest of the five answered; later I found out his name was Darko. He was holding my father’s pistol. They had come to search for hidden weapons, they said, and had found the pistol my father kept as a memento of his career. “What do you want with this gun? You, Yugoslav – what’s with the gun?” Darko was shouting and hitting my old man in the chest with the grip of the pistol. He didn’t react, but I rushed up to stand between the two of them. Darko shifted the pistol to his left hand and slapped my face with his right. I was boiling over with a seventeen-year-old’s fury, but my old man stopped me from pushing in front of Darko again. My mother held on to me.

‘“Where do you think you’re going, little Chetnik?” Darko remarked to me and then turned again to my father. “Were you keeping this gun for him? To fire at us?”

‘“No. It’s a memento. I’m a pensioner.”

‘“A pensioner? And where did you work. Eh?”

‘The old man was silent. He realised they knew he’d been in the Yugoslav army. They obviously knew all about him, and his wife and children as well. Now Darko slapped him in the face too, and he didn’t look up, so Darko wouldn’t see his eyes. Then one of the others in the group came up in front of Darko.

‘“We’re confiscating the gun. We can’t let everyone in town be armed.”

‘“Alright,” the old man answered, his gaze fixed on Darko, who had gone up to the door of my sister’s room.

‘“All of you – it would be best for you to leave town. We only came to search the place. But there are those who come for other reasons.”

‘“Alright,” the old man replied, still watching Darko, who opened my sister’s door, went inside and shut the door again.

‘“Are we agreed?” the polite one asked.

‘“Yes, we’re agreed.

‘“Look at me, so I can see we understand one another.”

‘My old man shifted his gaze from the door of my sister’s room and looked at the polite one.

‘“Good, now we’ll search the flat for any other weapons and then we’ll leave you to pack your bags. While we’re searching, you sit down here nicely and drink your morning coffee,” he gestured towards the table.

‘We sat down, and the four young men began to rummage aimlessly through our drawers and cabinets. One went into my room and dug through everything there. Another made a mess in my parents’ bedroom. The other two rummaged around in the lounge room and the kitchen. No one went into my sister’s room. Neither did anyone come out.

‘It all lasted maybe another ten minutes, and then Darko opened the door my father had been staring at all the time without even blinking. The young men gathered together and left. The polite one, as he left, remarked to my old man to “be smart”, but he made no reply. He was still staring at my sister’s door. Finally she came out, white-faced and with shaking legs, and went to the bathroom. She didn’t speak to any of us, and none of us asked her anything. Ever.

‘We slept in the flat for another two nights, and then we all went by car to Zagreb. My father’s friend let us sleep at his place until he left for Germany.’